A new menace has emerged on the cybercrime landscape — the VanHelsing operation, built on the Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) model. Since its inception on March 7, 2025, the group has already claimed responsibility for three successful attacks, demanding ransoms of up to $500,000. With its adaptable approach and extensive capabilities, the project is rapidly gaining traction among cybercriminals.

The essence of the RaaS model lies in its division of labor: malware developers lease their tools to affiliates who execute the attacks. In VanHelsing’s case, the buy-in is $5,000, though vetted threat actors may gain access for free. Affiliates retain 80% of the ransom, while the operators take the remainder. The only restriction, in keeping with industry norms, is a ban on targeting countries within the CIS.

VanHelsing’s functionality spans a broad spectrum of platforms — Windows, Linux, BSD, ARM, and ESXi — and employs a double extortion strategy: first exfiltrating data, then encrypting it. Victims are threatened with public exposure of their stolen information should they refuse to pay.

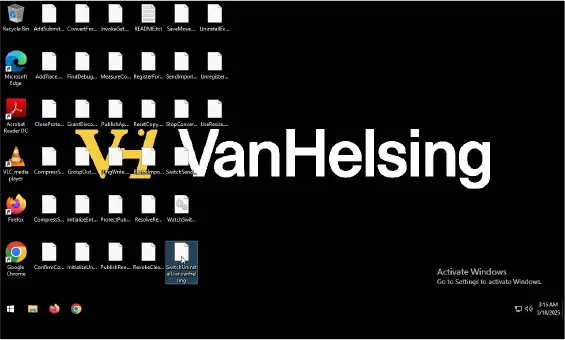

One of VanHelsing’s notable features is its sophisticated control panel, accessible on both desktop and mobile devices. Written in C++, the malware deletes shadow copies upon execution, scans local and network drives, and encrypts files with the “.vanhelsing” extension. It also changes the victim’s desktop wallpaper and delivers a ransom note demanding payment in Bitcoin.

The malware supports command-line interaction, allowing attackers to fine-tune parameters: selecting encryption modes, specifying directories to target, enabling SMB propagation, or activating a “silent” mode in which filenames remain unchanged.

According to cybersecurity firm CYFIRMA, early victims included governmental, manufacturing, and pharmaceutical organizations in France and the United States. Given its intuitive interface and frequent updates, VanHelsing is already regarded as a formidable weapon in the cybercriminal arsenal despite its recent debut.

Its rise coincides with a broader surge in ransomware activity. New variants of Albabat have been observed targeting not only Windows but also Linux and macOS, collecting system and hardware information. Simultaneously, the group BlackLock — formerly known as Eldorado — has intensified operations, becoming one of 2025’s most aggressive actors. Their campaigns have targeted the technology, construction, finance, and retail sectors. The group actively recruits traffers — operators who lure victims to malicious sites to establish initial access.

Cyberattacks are increasingly evolving from the domain of specialized hackers into a commodified service, complete with user-friendly interfaces, flexible terms, and structured profit-sharing. Platforms like VanHelsing blur the line between organized cybercrime and opportunistic exploitation.

The ease of participation, process automation, and high profitability render the ransomware market ever more alluring — and ever more difficult to defend against. The threat now emanates not from isolated groups, but from a vast ecosystem in which anyone can become an attacker.