As solar panels steadily become a fixture of daily life—enhancing energy resilience and reducing our carbon footprint—their digital infrastructure is increasingly marred by vulnerabilities. Researchers at Forescout have uncovered a sweeping issue: more than 34,500 solar energy management devices remain exposed to the internet and susceptible to potential cyberattacks. These include inverters, data loggers, monitors, gateways, and other components from 42 manufacturers.

This openness, while born of convenience—users wishing to access real-time energy production statistics online—has become a double-edged sword. What simplifies life for owners also simplifies exploitation for malicious actors. Through platforms like Shodan, anyone can locate these connected devices and, armed with known vulnerabilities, launch attacks.

According to the report, Forescout identified 46 newly discovered vulnerabilities and documented 93 previously known ones. Alarmingly, some of these flaws date back at least a decade. For instance, SMA Sunny Webbox inverters still contain a hardcoded vulnerability first reported in 2014.

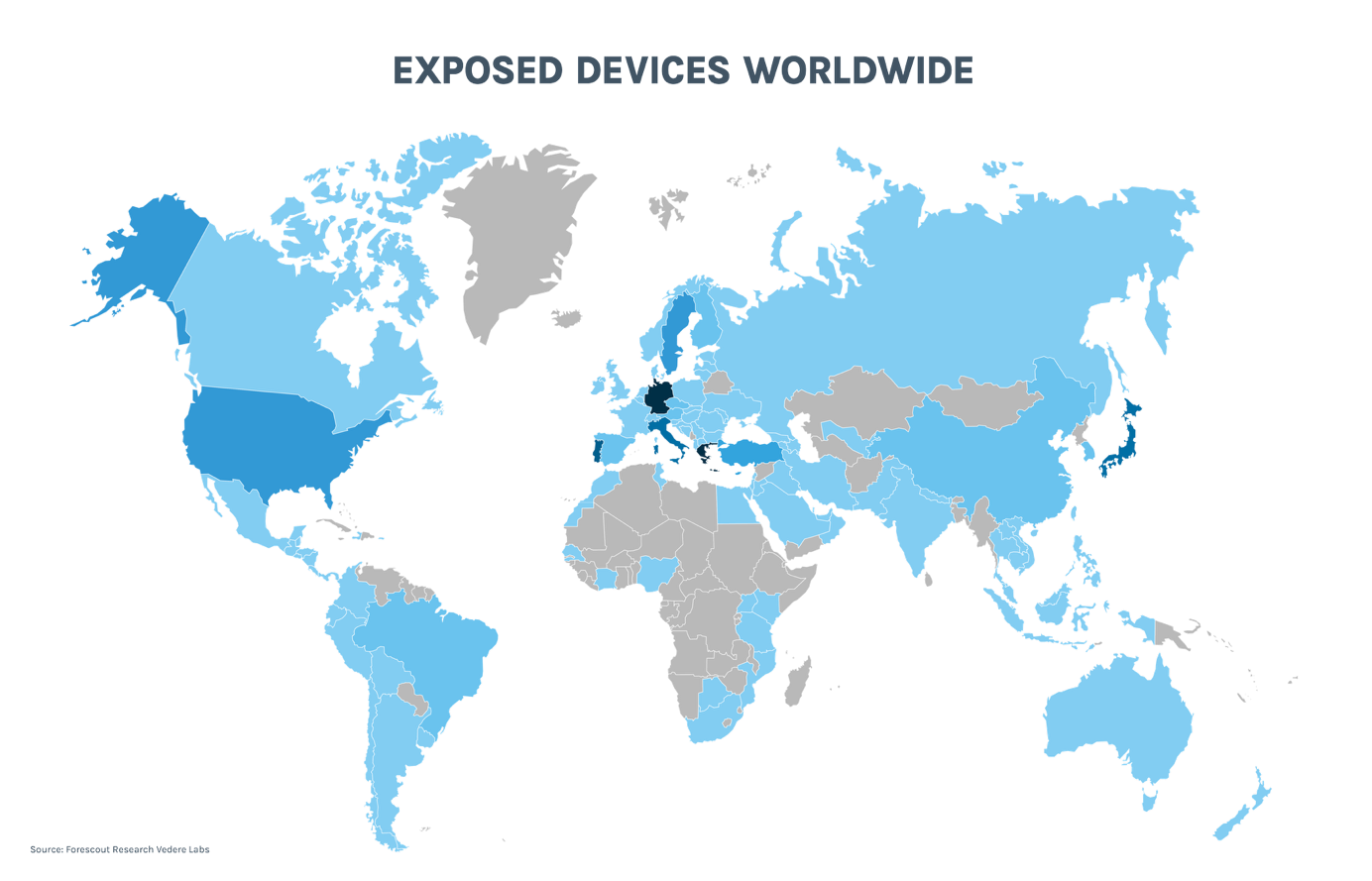

Among the most exposed manufacturers are SMA Solar Technology (12,434 devices), Fronius International (4,409), Solare Datensysteme (3,832), Contec (2,738), and Sungrow (2,132). Notably absent from the list are market giants like Huawei and Ginlong Solis—suggesting that vulnerability is not solely a function of market share but often stems from specific device architecture and user configuration.

The geographical distribution of the issue is heavily skewed toward Europe, where 76% of vulnerable systems are located. Germany and Greece alone account for 20% each, followed by Asia (17%), the Americas (5%), and the rest of the world (2%). This European concentration reflects both the region’s higher adoption of solar technology and the unique nature of local network configurations.

Experts emphasize that simply being internet-accessible is not inherently a flaw—it often results from deliberate IT configurations such as port forwarding. Despite manufacturers advising against exposing control interfaces online, many users continue to do so.

Forescout also recorded activity from at least 43 IP addresses targeting SolarView Compact devices. All of these attacks exploited outdated firmware, with none of the devices running current versions. The attacking IPs ranged from known botnet nodes to Tor exit nodes, indicating a wide spectrum of threats—from automated scans to anonymized assaults.

In light of incidents like the massive blackout in Spain, the specter of remote shutdowns of solar infrastructure becomes especially concerning. Experts warn that the proliferation of vulnerable inverters could jeopardize the stability of entire energy grids. As long as firmware updates remain unapplied and interfaces left exposed, these devices risk being weaponized in cyberattacks.

Forescout urgently recommends severing direct internet connections to such devices, instead employing VPNs or segmented network architectures, and ensuring prompt firmware updates. Without such measures, tens of thousands of systems worldwide will remain potential entry points for cybercriminals.

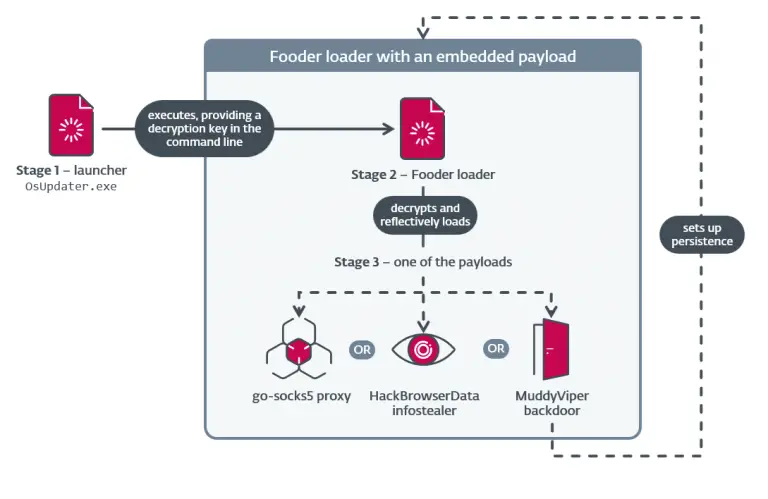

Amid these revelations, prior reports resurface regarding certain Chinese-manufactured solar devices containing “inexplicable communication hardware”—only adding further uncertainty to the cybersecurity landscape of the global energy sector.