The young men in the photographs are smiling, playing football, sipping sparkling wine, and posing beside swimming pools and cardboard Minions. At first glance, the images resemble ordinary snapshots from a developers’ teambuilding retreat. But these individuals are neither from Silicon Valley nor Berlin. They are North Korean IT workers embedded in Western companies with a singular objective: to generate hard currency for Kim Jong Un’s regime.

Experts at DTEX have uncovered the identities of two individuals, allegedly operating under the aliases Naoki Murano and Jenson Collins. According to the company’s findings, they initially worked from Laos before relocating to Eastern Europe. Murano had already been implicated in prior investigations; last year, he was linked to the theft of $6 million from the crypto platform DeltaPrime. Collins, for his part, was reportedly involved in blockchain projects believed to be entirely orchestrated from within North Korea.

DTEX has published over 1,000 email addresses that it claims are associated with the activity of North Korean IT operatives. This disclosure marks one of the largest attempts to illuminate the extent of their infiltration into the global digital economy. The investigation revealed that many of these addresses belong to fabricated personas lacking any genuine digital footprint, yet registered on platforms for freelancers and developers.

Kim Jong Un has long transformed the digital industry into a cornerstone of his regime’s financial architecture. Beyond the well-documented hackers engaged in cryptocurrency theft and espionage, thousands of IT specialists masquerade as freelancers from other nations. Many of them are trained from an early age and maintain long-standing connections. Despite their high level of technical proficiency, they often leave behind digital traces: overlooked code comments, exposed repositories with résumés, and inconsistencies in forged biographies.

According to DTEX, Murano and Collins were members of a development collective referred to as “Misfits”—photographs of the group were discovered in an unsecured Dropbox account. Analysts monitoring North Korean cyber activity compiled the images. In one, Murano is seen posing with a steak dish; in another, Collins relaxes by a pool. One particular photo depicts a man in a room with three uniformed military personnel and actively used computers. A surveillance camera on the wall and visible WhatsApp chats suggest comprehensive oversight by North Korea’s Ministry of State Security.

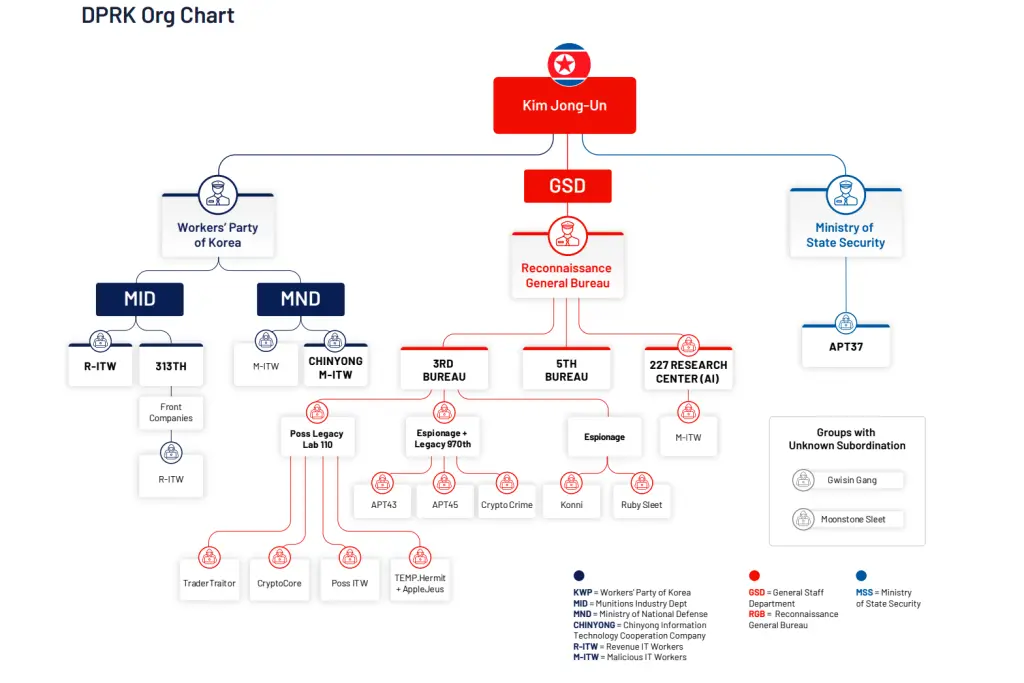

As outlined by DTEX, segments of these IT operatives are connected to military units, others to the Ministry of Defense, and some to the industrial department tasked with weapons development. There also exists an AI-affiliated entity—Unit 227 Research Center—operating under the General Reconnaissance Bureau. These workers are subjected to financial quotas, with only a small portion—roughly $200 out of $5,000—remaining in their hands. The rest is funneled directly into North Korea’s state treasury.

All of this unfolds against a backdrop of mounting pressure from the United States. In 2023, sanctions were imposed on the Chinyong Information Technology Cooperation Company; in 2024, additional measures targeted firms operating in China and Laos. According to the U.S. Treasury, North Korean IT groups generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually for the regime.

Recently, North Korean IT operatives have increasingly resorted to facial obfuscation—using neural networks to alter their appearances in photos and video calls. One such example is a fictitious developer named Benjamin Martin, whose face analysts believe to be a digital composite of a real individual. The companies listed on his résumé deny any affiliation, and when contacted via Telegram, he tersely responded in Chinese, admitting to being a North Korean IT worker.

DTEX emphasizes that all observed groups exhibit remarkable agility and adaptability. In the wake of each exposure, new layers of obfuscation emerge—fresh personas, surrogate identities, and networks of front companies. Until Western firms develop more robust methods for vetting remote employees, North Korea will continue to exploit the digital economy to sustain its authoritarian regime.