The Netherlands has enacted a new law establishing criminal liability for modern forms of espionage, including digital surveillance and efforts to influence members of diaspora communities. The vote in the Eerste Kamer (the upper house of parliament) took place on March 18. The legislation amends the Criminal Code, bolstering protections for national security, critical infrastructure, advanced technologies, and the country’s population.

As explained by Justice and Security Minister Dilan Yeşilgöz-Zegerius, coordinated actions carried out on behalf of foreign states have become increasingly commonplace, necessitating enhanced resilience against external threats. The new law, she emphasized, sends a clear message: the Netherlands will not tolerate espionage and will respond to it with unwavering resolve.

Previously, Dutch legislation provided for punishment in cases of traditional espionage, such as the transmission of state secrets. However, the threat landscape has evolved. Under the new provisions, even the dissemination of non-classified information may constitute an offense if it serves the interests of a foreign state and poses a serious risk to the Netherlands. This includes, for example, proprietary business data, personal information, or intelligence that could be exploited to interfere in political processes.

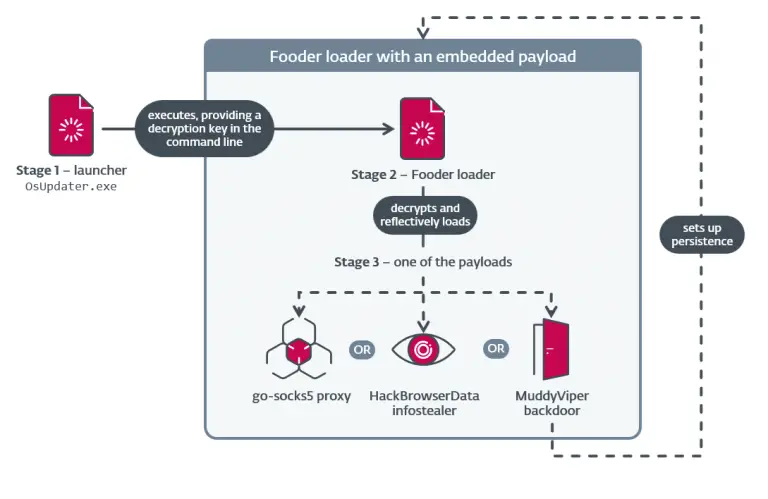

According to the revised statute, engaging in activities on behalf of a foreign power that inflict harm on the Netherlands may be punishable by up to eight years in prison. In particularly grave cases—such as when such espionage leads to loss of life—the sentence may extend to twelve years. Penalties for crimes involving cyberattacks committed in the interest of another nation have also been intensified, with aggravating factors now including hacking, bribery, and other espionage-related acts.

The interests of foreign intelligence services now extend far beyond matters of state secrecy. Special attention is being paid to information concerning economic sectors, political decision-making, technological innovation, and diaspora communities. Such data may be weaponized to destabilize economies, exert political pressure, or sow discord among allied nations. Additionally, forms of influence that do not directly involve data theft—such as sabotage or interference in decision-making—are also within the law’s purview.

The legislation also places emphasis on protecting individuals with migration backgrounds, who may be subjected to coercion or intimidation by foreign states. The inclusion of diaspora espionage represents a new focal point in Dutch national security policy.

At the same time, the law makes clear that casual interaction or cooperation with foreign entities is not prohibited. Only deliberate involvement in activities that harm the interests of the state may be deemed espionage.