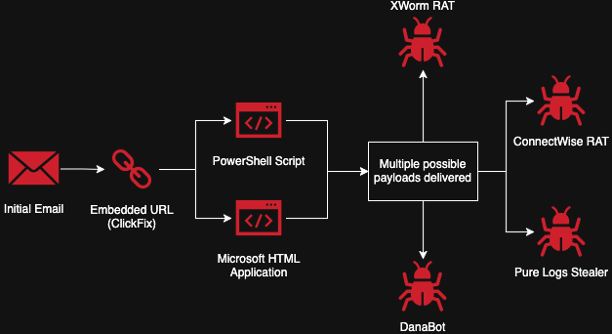

An attack chain diagram for a typical sample in this campaign

At first glance, it appears to be nothing more than a routine security check. In reality, it is a deftly disguised trap, leading unsuspecting users straight into the hands of cybercriminals. Researchers at CloudSEK have identified a new wave of macOS-targeted attacks employing social engineering through counterfeit CAPTCHA pages and malicious scripts. The infection vector follows a method known as ClickFix—a technique rapidly gaining traction among spyware distributors.

This latest campaign revolves around the well-known malware Atomic macOS Stealer (AMOS), already familiar to security analysts. This time, it is being disseminated through websites masquerading as official portals of the U.S. telecom operator Spectrum. Domain names such as panel-spectrum[.]net and spectrum-ticket[.]net are crafted to closely mimic legitimate addresses, thereby enhancing the illusion of authenticity.

When a user visits one of these sites, they are prompted to perform a connection check via hCaptcha—allegedly to ensure their traffic has not been intercepted. After clicking the familiar “I’m not a robot” checkbox, an error message appears. The site claims the verification failed and offers an “alternative method”—a button that, when clicked, copies a command to the user’s clipboard.

Illicit hacker knowledge—reserved for insiders.

Subscribe to us.

What happens next varies by operating system, but the objective is always the same: to trick the user into manually executing a malicious script. For macOS, the site instructs the user to open Terminal and paste the command, which requests the system password. This initiates a chain of execution: first, a shell script runs, followed by the download and execution of the second stage—AMOS.

AMOS is an information stealer designed to harvest passwords, autofill data, cryptocurrency wallet credentials, and other sensitive information. The script leverages native macOS utilities to bypass built-in security mechanisms, gain access to system-level data, and execute binary files without alerting the user.

Analysis of the source code revealed comments written in Russian, suggesting possible involvement of Russian-speaking threat actors. This detail also supports the suspected origin of the attack infrastructure and the methodology employed.

Researchers also noted numerous logical flaws on the malicious pages. For instance, Linux users were presented with PowerShell commands, which are incompatible with that platform. Both Windows and macOS users were told to press Win+R—an instruction meaningless on Apple devices. These inconsistencies hint at a rushed deployment, likely driven by urgency to launch the campaign before detection.

Yet, despite such flaws, the ClickFix technique remains alarmingly effective. It exploits users’ habitual tendency to hastily bypass verification prompts and warnings. A fake CAPTCHA or cookie consent pop-up rarely raises suspicion—especially when rendered with pixel-perfect precision.

ClickFix has already proven its efficacy. Over the past year, dozens of variants have been documented. In one April 2025 incident, attackers used this method to stealthily deliver malware capable of lateral movement within networks, gathering configuration data and exfiltrating it via HTTP requests to external servers.

Delivery mechanisms vary—from phishing emails to compromised websites. In a campaign uncovered by Cofense, attackers impersonated Booking.com to target the hospitality and restaurant sectors. The phishing emails contained links to CAPTCHA pages hiding scripts that launched XWorm, DanaBot, and PureLogs wipers.

In some cases, malicious scripts are injected not via CAPTCHA, but through counterfeit cookie consent banners. Again, a user clicking “Accept” unwittingly downloads an executable file, believing they are performing a harmless setup.

Other attacks mimic well-known verification services like Google reCAPTCHA and Cloudflare Turnstile. Threat actors embed malicious code into these elements or insert them into already compromised websites. Popular payloads include Lumma Stealer, StealC, and full-fledged remote access tools like NetSupport.

CloudSEK and other cybersecurity firms have confirmed ClickFix attacks are active across Europe, the United States, the Middle East, and Africa. The geographic footprint continues to expand, as do the techniques used. Yet the underlying goal remains unchanged.

The true vulnerability exploited by these campaigns lies not in the software, but in human behavior. Users have become numb to the endless stream of verifications, prompts, and consent windows—and eventually, they stop paying attention to what they are agreeing to.

Defending against such deception is especially difficult because it all appears so familiar, so convincingly routine. Antivirus solutions may not detect commands executed manually by the user. Firewalls are equally ineffective if the script employs native macOS or Windows functions.