The Iranian threat group MuddyWater has significantly expanded its toolkit and refined its tactics, conducting a series of targeted attacks against organizations in Israel and one company in Egypt. ESET researchers observed the deployment of entirely new tools, most notably the Fooder loader — a component that not only executed malicious code but also disguised itself as the classic game “Snake,” concealing its true purpose and misleading analysis systems. The campaign showcased an uncharacteristic level of stealth and technical maturity for MuddyWater.

According to ESET, MuddyWater — also known as Mango Sandstorm or TA450 — one of Iran’s most active APT groups, abandoned its usual noisy methods. Instead of manual commands and crude interactions with compromised systems, the attackers adopted a more precise and discreet approach, focusing on quiet persistence and data theft.

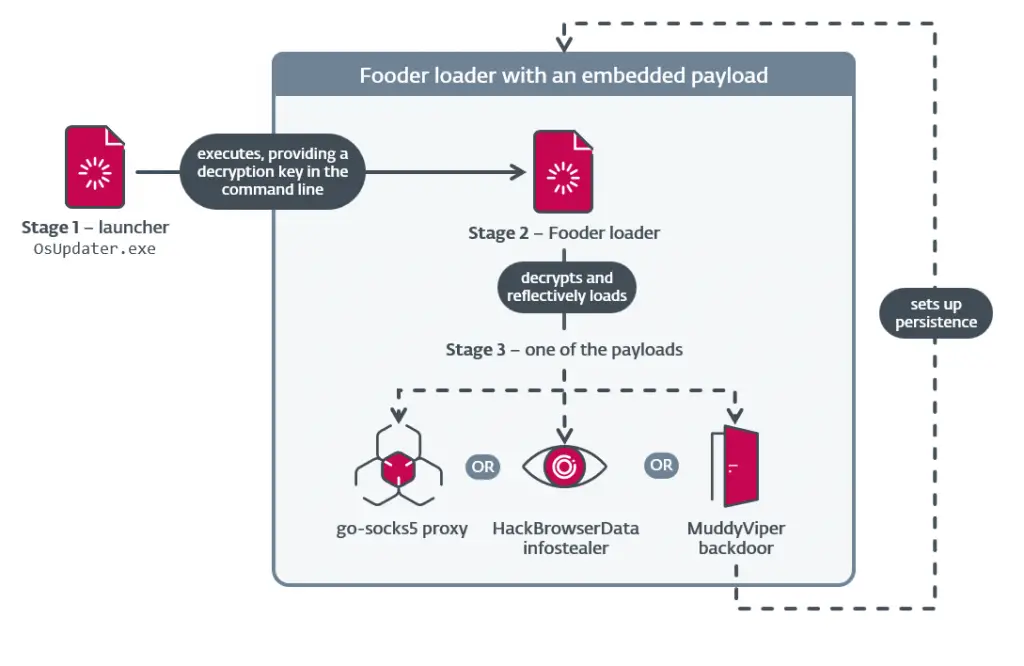

At the heart of the operation was the new C/C++-based Fooder loader. It reflectively loaded payloads directly into memory, reducing detection risk. Several variants were disguised as a simple Snake game: the code contained game strings, interface elements, and even loop logic mimicking the snake’s movement. This masquerade served two purposes — it misled superficial analysis while introducing long execution delays that made the malicious activity less noticeable to sandboxes tuned for short-lived behaviors. Through Fooder, the newly developed MuddyViper backdoor entered the system, capable of executing commands, opening reverse shells, uploading and downloading files, collecting system information, and stealing credentials.

Alongside MuddyViper, attackers used a suite of specialized tools: the CE-Notes and LP-Notes credential thieves, the Blub browser stealer, and enhanced go-socks5 reverse tunnels. Researchers note an unusual detail — the active use of CNG, the modern Windows cryptographic API, which is rarely seen among Iran-linked threat groups.

The operation ran from September 2024 to March 2025. Its victims included engineering, manufacturing, transportation, technology, and educational organizations in Israel, as well as a single technology entity in Egypt. An additional twist was MuddyWater’s temporary cooperation with another Iranian group, Lyceum. After the initial breach, credentials obtained by MuddyWater were reportedly leveraged by Lyceum to move deeper into a manufacturing-sector victim. This suggests MuddyWater may be acting as an initial-access broker.

Although MuddyWater has long been known for simple tools and predictable methods, this campaign marks a clear evolutionary step: more complex loaders, game-based obfuscation, expanded cryptography, and a more deliberate attack architecture. Yet the group remains consistent in its choice of targets — government entities, critical infrastructure, telecommunications, and other strategically significant sectors.

ESET assesses that MuddyWater is likely to continue expanding its toolkit and strengthening the technical sophistication of its operations, conducting increasingly quiet, intricate, and multi-layered attacks. Researchers will be watching closely for the group’s next evolutionary turn and the emergence of new components in its arsenal.