The soaring popularity of Kling AI, a platform capable of generating images and videos from text and graphic prompts, has given rise to a serious cyber threat. According to experts at Check Point, fraudulent Facebook pages and sponsored posts bearing the Kling AI logo are directing users to malicious clone websites, luring them with promises of generative capabilities. Instead of receiving creative media, victims unwittingly download remote access trojans and malware engineered to steal sensitive personal data.

Launched in June 2024 by Chinese firm Kuaishou Technology, Kling AI had amassed over 22 million users by April 2025. Capitalizing on this momentum, cybercriminals initiated a campaign grounded in social engineering, deceptive websites, and intricately crafted decoys disguised as harmless media files.

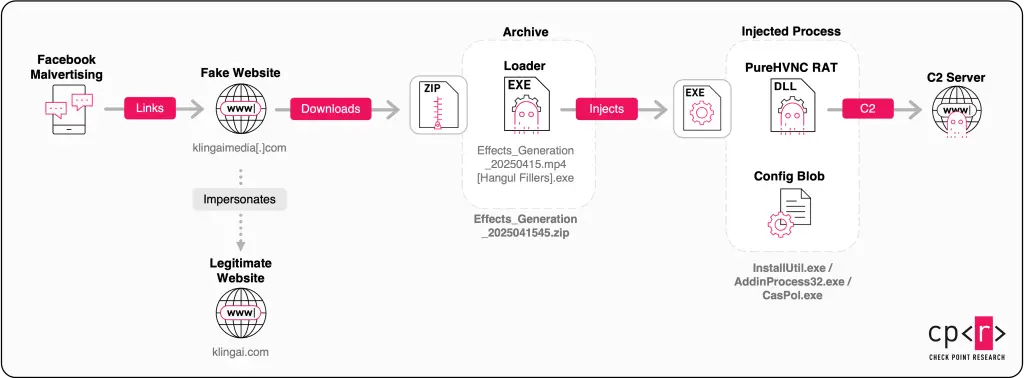

Malicious activity was first observed in early 2025. Victims are enticed to domains such as klingaimedia[.]com and klingaistudio[.]com, where they are offered instant image or video generation. However, the downloadable file is, in fact, a Windows executable with a double extension and concealed Unicode characters, specifically designed to evade antivirus detection.

The downloader initiates a chain of attacks: it installs a Remote Access Trojan (RAT), an infostealer, and establishes a connection to a command-and-control server to exfiltrate credentials, session tokens, and cryptocurrency wallet contents from Chromium-based browsers. It also captures screenshots when users access banking or crypto platforms, deploying these functions via a modular plugin system.

What makes these attacks particularly insidious is their sophistication in avoiding detection. The loader scans for analysis tools such as Wireshark, Procmon, or OllyDbg, modifies Windows registry entries for persistence, and injects a secondary payload into legitimate system processes like CasPol.exe or InstallUtil.exe.

The second-stage payload, protected by .NET Reactor, is PureHVNC RAT—a powerful remote access tool that operates via the server 185.149.232[.]197. It enables full control over the compromised machine, facilitating comprehensive data theft.

Check Point has identified at least 70 promoted posts originating from fake Kling AI pages, pointing to a possible Vietnamese connection—with various elements on cloned websites and ad banners bearing indicators of Vietnamese origin.

The tactic of distributing malware through Facebook advertising is far from new. Vietnamese groups have previously been linked to campaigns masquerading malware as AI tools. Notably, in early May, Morphisec reported a campaign involving the Noodlophile infostealer, also disguised as a generative service.

This wave of deception unfolds against the backdrop of rampant fraud proliferating across social media platforms. As reported by The Wall Street Journal, Meta is grappling with an “epidemic of deceit,” as its platforms are inundated with ads for fake lotteries, fraudulent romantic schemes, and counterfeit sales events. Many of these campaigns are orchestrated from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka.

Meanwhile, according to Rest of World, fictitious job offers circulated on Facebook, Telegram, and similar platforms are being used to recruit young Indonesians, who are subsequently trafficked to scam compounds in Southeast Asia, where they are coerced—under threat of violence—into executing fraudulent investment operations.

The Kling AI impersonation campaign is merely one example of a broader, insidious trend: a new wave of attacks combining social engineering, sophisticated malware, and deceptive advertising—turning social media into a principal vector for infection and exploitation.