When the conversation turns to hackers, the imagination often conjures images of digital chaos—individuals who breach systems for profit, amusement, or ideology. Yet, behind many of these stories lies something far more complex: psychology, internal conflict, and choices made at the very edge of acceptability. One former member of the shadowy hacking community has chosen to share his past, underscoring that true strength lies not only in technical prowess, but in the ability to stop oneself in time.

In the mid-2000s, he took part in numerous operations that granted him access to major servers and infrastructure across various industries. Yet, his goal was never destruction or total domination of networks. What mattered more was retaining control over his own actions and environment. If the outcome seemed unpredictable, he would refrain from interference. In his words, this is what separates those who hack out of curiosity from those who pursue consequences at all costs.

One such episode occurred in 2008. Alongside a fellow hacker, he accessed an internet service provider’s server via remote desktop—the breach was surprisingly easy, as the password matched the username. Installed on the server was software for managing satellite terminals, including the once-popular HN7000S and DW7000 modems operating on VSAT systems. Such technology is often used in remote regions and supports business, governmental, and even military communications.

Rather than exploiting the infrastructure to inject malicious code or seize control of satellite channels, they opted not to take the risk. The decision not to act was deliberate—the level of uncertainty was too high, and the slightest error could have had serious repercussions. Ultimately, the server was used merely to store illicit content—a compromise between temptation and restraint.

Another incident took place in the early 2000s, when the group gained access to a bank’s infrastructure. At the time, many institutions still relied on outdated protocols like Telnet, which transmitted data in plain text. The hackers connected to one such bank via terminal access, using administrator credentials. They soon discovered they were inside the bank’s Security Operations Center (SOC), located directly within its data center. From that point, they had nearly unrestricted access to the internal network.

Paradoxically, this access was granted not by technical ingenuity but by the administrator’s negligence—he had been idly browsing explicit websites instead of monitoring the system. The hackers could have stolen funds, altered system configurations, or exfiltrated sensitive data. Instead, they chose to merely observe, capturing network traffic for later analysis. As the narrator recalls, the money in the bank was insured—but behind it were real people, their time, their labor, and their hopes. It was one of those moments when the awareness of real-world harm outweighed the allure of profit.

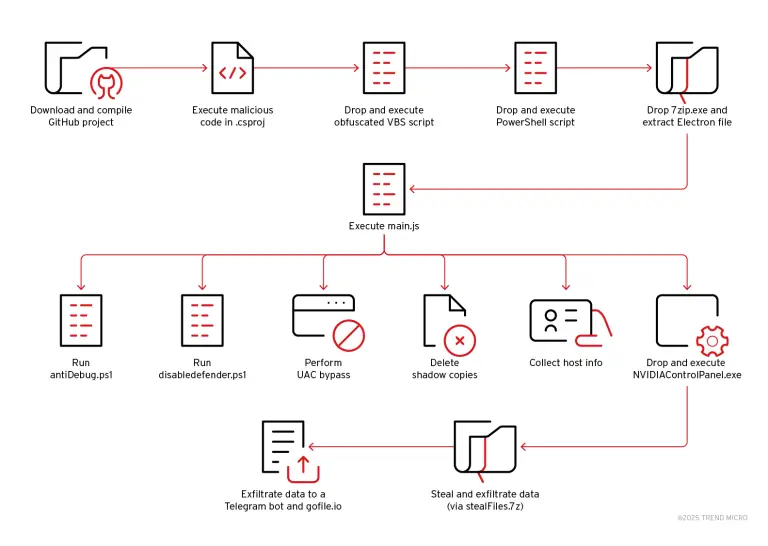

However, avoiding consequences wasn’t always possible. In 2009, in an attempt to expand their botnet, the group deployed malicious firmware to widely used DSL modems. Using a Python script, they automated the installation of modified firmware on vulnerable devices. In theory, this would create a distributed network of controllable nodes. In practice, it proved disastrous. Lacking a proper understanding of the hardware architecture and original codebase, the new firmware rendered devices inoperable—they would no longer power on and were beyond recovery.

Over 100,000 modems in Brazil were rendered useless. The campaign became one of the earliest known examples of a phlashing attack—a type of denial-of-service that physically destroys devices by corrupting their firmware. According to the hacker, the full impact didn’t dawn on them immediately. At the time, they simply dismissed it as a failed experiment and moved on to another target. The responsibility for the broken hardware and the people left without internet access wasn’t taken seriously.

Over time, as he matured, his perspective shifted. He increasingly questioned whether every vulnerable service truly warranted exploitation. Many in the hacking community justify their actions as a way of “teaching” system owners about proper security. But in reality, such rationalizations often mask a simple craving for validation and the thrill of transgression. The refusal to attack, he now believes, is a sign of maturity—not weakness.

He emphasizes that the mere ability to hack does not justify the act itself. A hack executed without purpose, without comprehension of its consequences, and without a willingness to bear responsibility—is not a demonstration of strength, but its illusion. True power, he concludes, lies in knowing when to walk away.