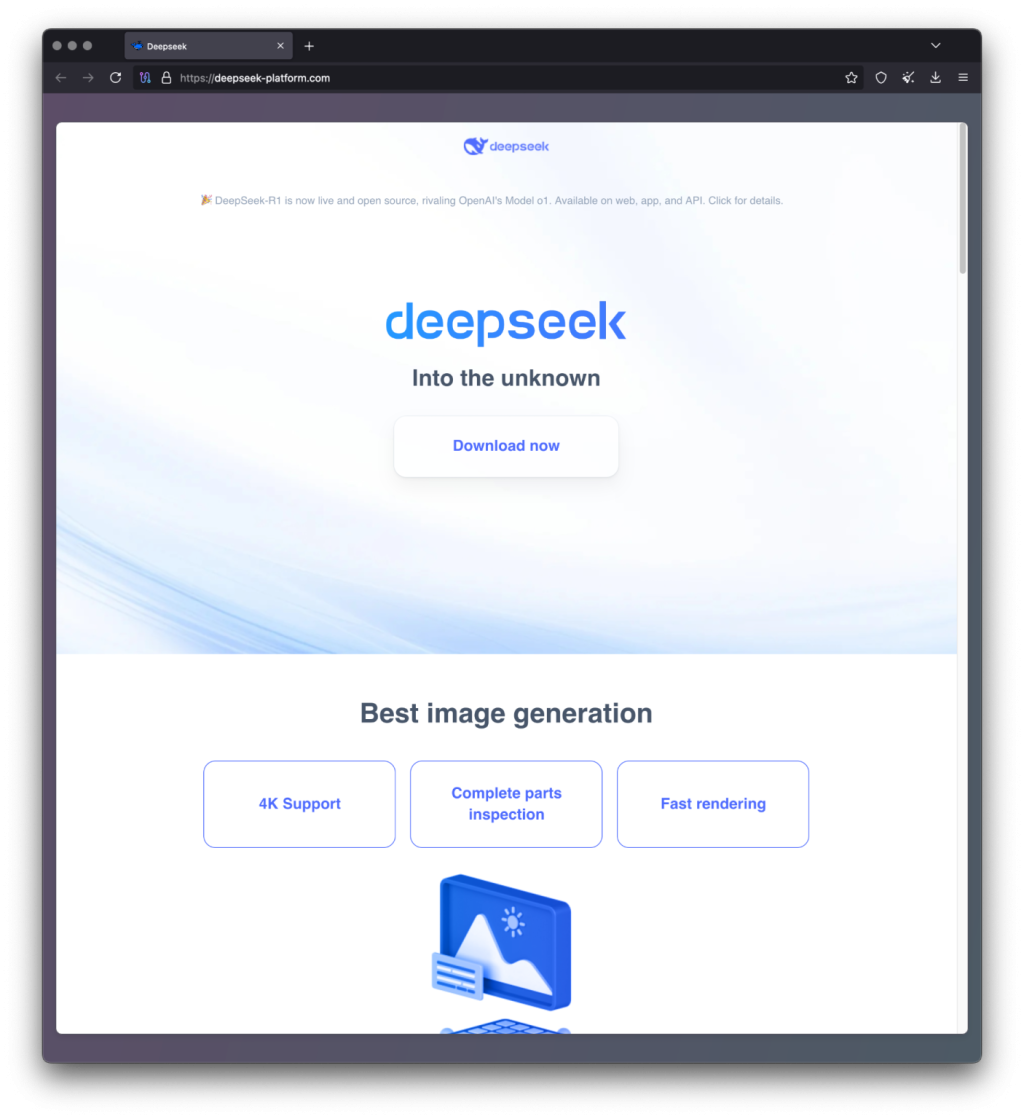

As the popularity of language models continues to surge, cybercriminals are increasingly exploiting this momentum to orchestrate sophisticated attacks. A recent malicious campaign has targeted DeepSeek-R1—one of today’s most sought-after AI tools. Users, in their pursuit of a chatbot based on this model, often fall prey to deceptive websites masquerading as official platforms.

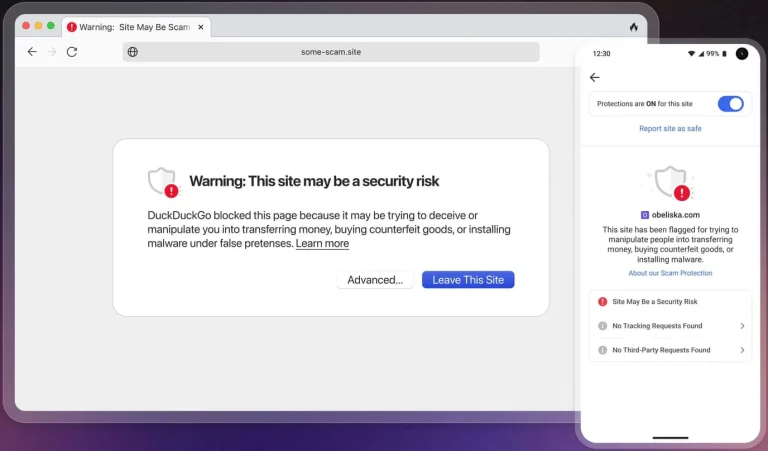

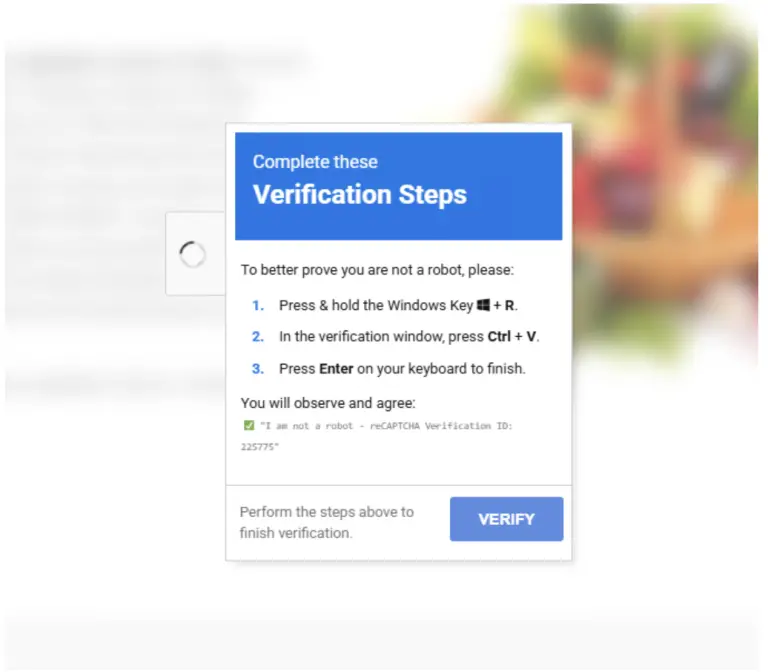

Researchers at Kaspersky Lab uncovered a new wave of attacks leveraging a counterfeit DeepSeek-R1 installer distributed through a phishing site aggressively promoted via Google Ads. Visually indistinguishable from the genuine site, the malicious page automatically detected the visitor’s operating system. For Windows users, a “Try now” button appeared, leading to a fake CAPTCHA page—purportedly to deter bots.

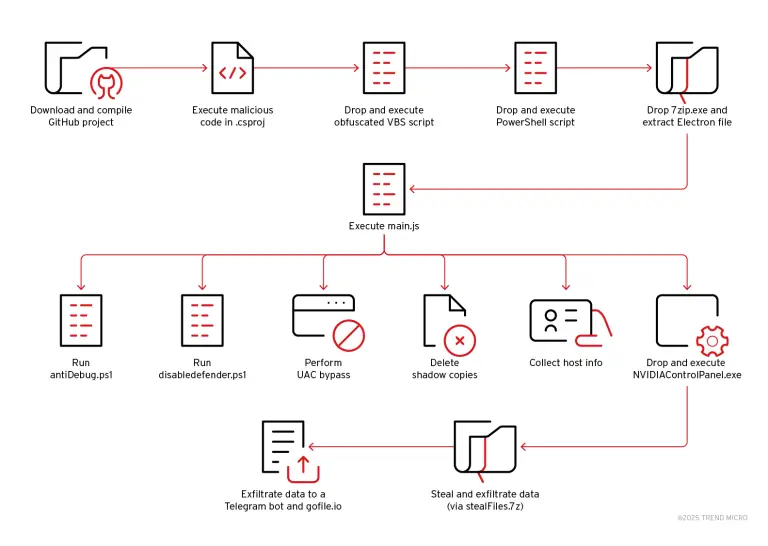

Upon completing the CAPTCHA, users were redirected to a “Download now” prompt, which initiated the download of an executable named AI_Launcher_1.21.exe from a separate fraudulent domain. Embedded within the installer was the next infection stage. When launched, the file presented another counterfeit CAPTCHA and feigned the installation of legitimate AI programs such as Ollama or LM Studio. Simultaneously, a concealed function—MLInstaller.Runner.Run()—was executed, triggering the malicious payload.

The initial stage deployed an encrypted PowerShell command designed to exclude the user’s folder from Microsoft Defender’s scanning scope. This command utilized AES-256-CBC encryption, with both the key and IV hardcoded within the malware’s body. Execution required administrative privileges to proceed.

Next, a second PowerShell script was launched, downloading a malicious executable from a domain generated via a basic Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA). The payload was saved as 1.exe in the “Music” folder and subsequently executed. At the time of analysis, only one domain—app-updater1[.]app—was active, though its functionality had already ceased, suggesting preparation for the next infection phase.

The third phase decrypted another embedded executable and executed it directly in memory. This component, dubbed BrowserVenom, emerged as the cornerstone of the entire operation. Its primary function was to intercept all internet traffic by reconfiguring the user’s browsers to operate through a proxy controlled by the attackers.

BrowserVenom first verified administrative privileges. If granted, it installed the attackers’ certificate into the system’s trusted root certification authorities. It then altered browser settings—Chromium-based browsers like Chrome, Edge, Opera, and Brave were reconfigured via the –proxy-server argument, while LNK shortcuts were automatically rewritten. For Firefox and Tor Browser, modifications were made directly to the user profile.

The attackers’ proxy server operated at 141.105.130[.]106 on port 37121. Additionally, browser User-Agent strings were appended with a campaign identifier (LauncherLM) and a randomly generated hardware ID (HWID), enabling the attackers to track victims.

Phishing page source code contained comments in Russian. The geographic distribution of infections underscored the campaign’s reach, with incidents reported in Brazil, Cuba, Mexico, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Egypt.

The threat, classified as HEUR:Trojan.Win32.Generic and Trojan.Win32.SelfDel.iwcv, demonstrates how effectively malicious actors are capitalizing on AI enthusiasm. The use of Google Ads to promote the malicious link makes the campaign particularly insidious, especially for unsuspecting users who fail to verify URLs or certificates of downloaded software.

To mitigate such threats, users must diligently verify whether a site genuinely belongs to the model’s developer. In today’s digital landscape, even top-ranking search results can lead to system compromise.