Hackers affiliated with the Play group exploited a zero-day vulnerability in Windows to breach an American organization. The flaw resided in the Common Log File System (CLFS) component, and the vulnerability—tracked as CVE-2025-29824—was only patched by Microsoft a month ago. By that time, however, it had already been actively weaponized by threat actors.

The Play group, also known by aliases such as Balloonfly and PlayCrypt, has been employing double extortion tactics since 2022: exfiltrating sensitive data prior to encryption to intensify pressure on victims. In this particular incident, the attackers reportedly gained initial access through a publicly exposed Cisco ASA firewall, before moving laterally to a separate Windows machine within the target infrastructure. The precise method of this pivot remains undetermined, according to researchers at Symantec who uncovered the attack.

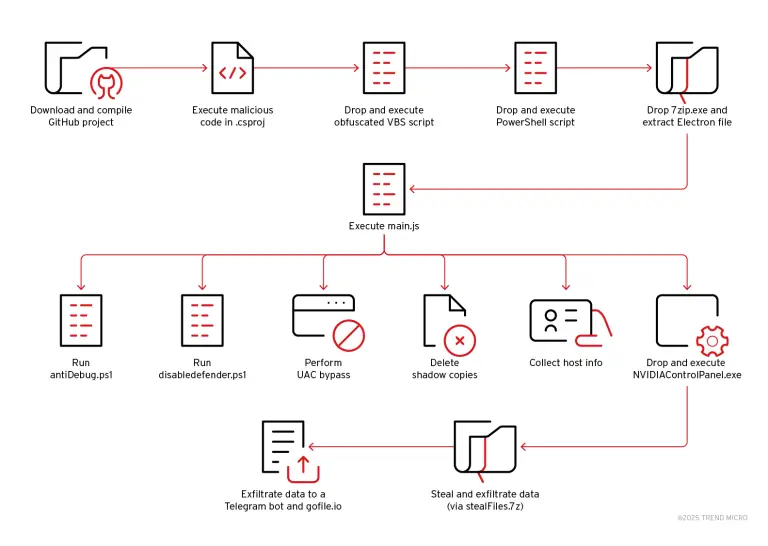

It was confirmed that a backdoor masquerading as Palo Alto Networks software was deployed on the compromised host. Files named “paloaltoconfig.exe” were in fact components of the malicious Grixba utility, previously attributed to the Play group by cybersecurity analysts. This module exploited CVE-2025-29824 and was discreetly placed in the system’s “Music” directory. Concurrently, the attackers conducted reconnaissance across Active Directory, collecting information on all domain-connected machines and exporting the results into a CSV file for subsequent analysis.

During exploitation, two key files were created: “PDUDrv.blf,” a CLFS base log signaling the use of the vulnerability, and “clssrv.inf,” a malicious DLL injected into the “winlogon.exe” process. This library executed two batch scripts. The first, “servtask.bat,” escalated privileges, extracted critical registry hives (SAM, SYSTEM, SECURITY), created a user account named “LocalSvc,” and added it to the Administrators group. The second, “cmdpostfix.bat,” was responsible for erasing traces of the intrusion.

Notably, no ransomware was deployed during the operation, suggesting the attack may have been part of a reconnaissance mission or a test run of the threat actors’ toolset. Experts believe the exploit for CVE-2025-29824 may have been circulating among multiple criminal groups prior to Microsoft’s official patch, significantly increasing the likelihood of further attacks.

It is also worth highlighting that the tactics described by Symantec differ from a separate incident in which Microsoft attributed exploitation of the same vulnerability to the Storm-2460 group and the PipeMagic trojan. This divergence underscores that CVE-2025-29824 has become a coveted asset among various hacking collectives, each wielding it for distinct purposes.

According to analysts, this case exemplifies a troubling trend: an increasing number of threat groups are leveraging zero-day vulnerabilities in ransomware-driven campaigns. Just a year earlier, the Black Basta group employed a similar method, using CVE-2024-26169—a flaw in the Windows Error Reporting Service—as a zero-day in its attacks.