Experts from Okta Threat Intelligence have conducted a comprehensive investigation into how operatives from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) secure employment within international IT companies. The findings are deeply alarming: generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has become a linchpin in elaborate employment fraud schemes, commonly referred to as “DPRK IT Workers” or “Wagemole.” Through GenAI, convincing digital personas are crafted, persuasive résumés are generated, interviews are passed—often with the aid of deepfakes—and individuals even manage to work multiple jobs simultaneously.

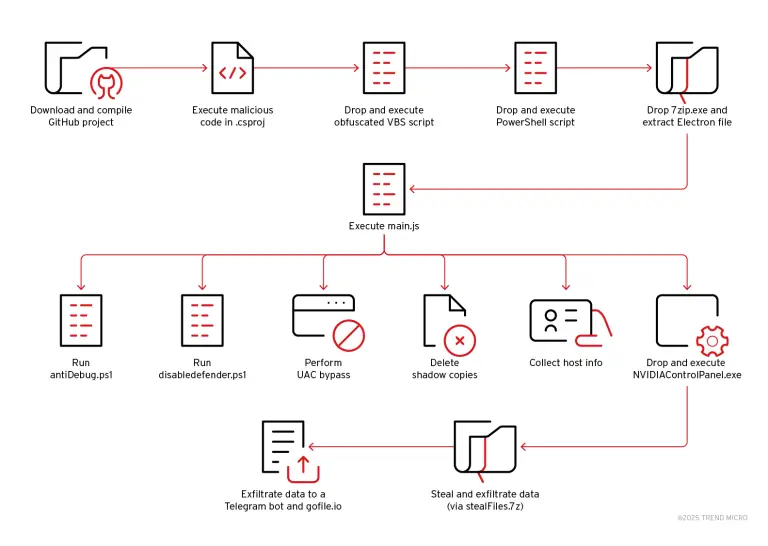

The objective of these operations is to circumvent sanctions and funnel foreign currency into the DPRK’s coffers. Behind the façade of legitimate remote workers lie entire teams orchestrated from so-called “laptop farms”—remote coordination hubs established in third countries. At these locations, facilitators—intermediaries in the scheme—receive, configure, and redistribute company-issued devices, manage correspondence on behalf of the candidates, and oversee their professional activities.

Such operations have been documented on U.S. soil as well. In 2024, authorities uncovered a scheme in which one facilitator established a “laptop farm” to aid North Korean operatives. In 2025, a group based in North Carolina was found to have successfully embedded dozens of DPRK-affiliated “employees” into American companies.

These campaigns are powered by a vast array of AI-driven tools capable of automating nearly every step of the employment process. Among them are services for résumé generation and validation, automated application form filling, and applicant tracking systems. Of particular significance are platforms that simulate HR behavior. Facilitators use these systems to post fake job listings in order to study which applications bypass automated filters and to refine counterfeit résumés accordingly. The insights gleaned from this process significantly increase the likelihood of North Korean candidates securing employment—essentially turning employers’ own tools against them.

One of the core challenges lies in managing communications for numerous fictitious personas simultaneously. For this, unified communication systems are employed, integrating email, messaging apps, and mobile accounts, along with tools for translation, transcription, scheduling, and interview coordination. This infrastructure enables facilitators to manage dozens of candidates while keeping their fabricated identities consistent and up to date.

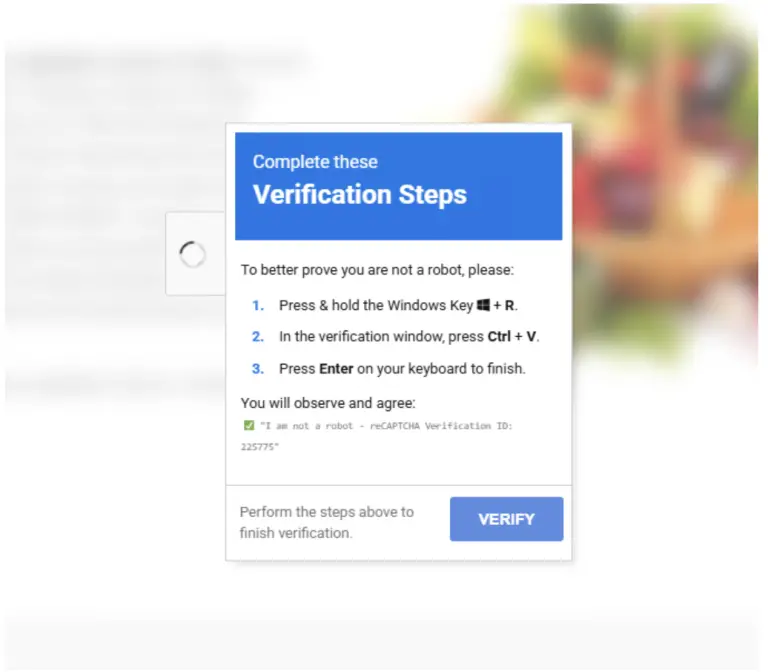

Upon successful advancement through recruitment stages, facilitators deploy neural networks to conduct mock video interviews, simulate interviewer reactions, and coach candidates on gestures, facial expressions, lighting, and presentation. At this phase, deepfake technologies—real-time face and voice masking—are tested to bypass visual verification checks, which are especially critical during video interviews.

Additional support is provided by generative chatbot services and rapid-learning platforms, enabling minimally prepared candidates to acquire fundamental knowledge of programming languages or technologies required for interviews or early-stage job performance. These same neural tools continue to assist post-hiring, helping maintain the illusion of technical competence.

Often, companies remain unaware that they are hiring “virtual employees.” Particularly vulnerable are technology firms that actively seek remote talent, as well as organizations lacking stringent identity verification protocols.

According to Okta, the scale of such operations means that even short-term employment can yield substantial revenue for the DPRK. GenAI and process automation have dramatically enhanced the efficiency of these campaigns—especially when executed at an industrial scale.

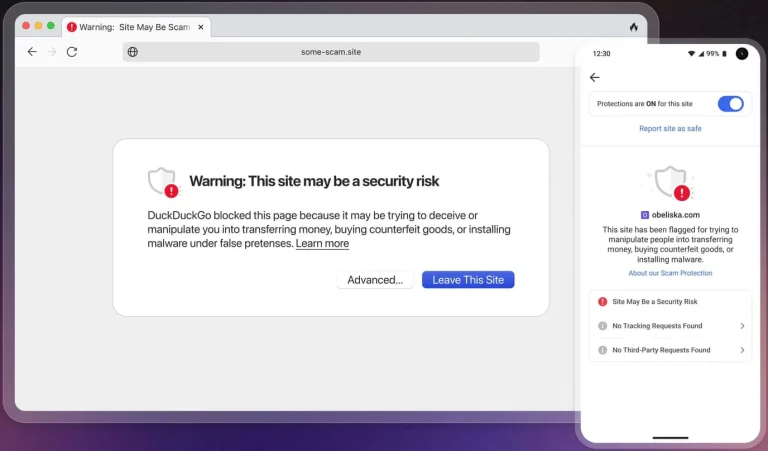

To mitigate the threat, Okta advises integrating identity verification procedures into business workflows, training staff to recognize signs of fraudulent activity, and monitoring unauthorized use of remote access tools.