Pakistan’s Supreme Council of Islamic Scholars has declared the use of VPNs incompatible with Sharia law, while the country’s Ministry of Interior has proposed a ban on the technology.

Raghib Naeemi, head of the Council of Islamic Ideology, stated that Sharia permits prohibitions on activities that lead to the “spread of evil.” According to Naeemi, platforms disseminating content that provokes controversy, insults religious sentiments, or undermines national unity should be immediately blocked.

Since February 2023, millions of Pakistani users have been deprived of access to the social media network X, which was banned by authorities ahead of parliamentary elections. VPNs, which conceal users’ online activity, remain the sole method of bypassing such restrictions. However, the Interior Ministry plans to outlaw VPNs, citing the need to combat extremism. Critics argue that these measures stifle freedom of expression.

While VPN usage is legal in most countries, nations with stringent internet controls often prohibit or restrict such services. In Pakistan, many VPN users support former Prime Minister Imran Khan, who is currently in custody. His supporters have called for a march on Islamabad to pressure authorities to release him. The government frequently shuts down communication services during rallies held by Khan’s followers. Nonetheless, Naeemi’s assertion that VPNs violate Sharia has sparked widespread debate.

Naeemi’s remarks followed a letter from the Ministry of Interior to the Ministry of Information Technology, urging a VPN ban. The letter alleges that terrorists increasingly use virtual private networks to promote their agendas and coordinate criminal activities. The ministry also seeks to block access to pornographic and blasphemous material.

Recently, internet users were required to register their VPNs with Pakistan’s media regulator, a move that could increase control over user activity.

Notably, the Pakistani IT company P@SHA recently accused the government of hastily implementing an internet firewall modeled on China’s system. Industry representatives argue that such measures were introduced without sufficient transparency and could severely damage the country’s IT sector, falling victim to “misguided priorities.”

Given Pakistan’s history of internet censorship, these accusations are not unfounded. On election day, the government imposed a complete internet blackout. This was not an isolated incident—Pakistan has previously restricted access to platforms such as Wikipedia, TikTok, and Twitter, often citing religious grounds.

A similar scenario is unfolding in Iran, where state media reports suggest that up to 80% of tech companies are considering emigration due to persistent internet restrictions.

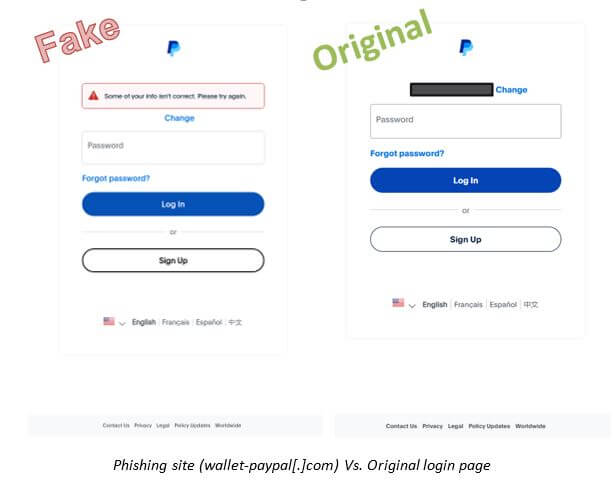

Pakistan’s actions in the digital sphere draw comparisons to China’s Great Firewall, which limits access to foreign websites, blocks VPNs and proxies, and employs techniques such as DNS spoofing and keyword-based URL filtering. However, unlike Pakistan, China maintains stable and fast access to domestic online resources despite its stringent measures.